In our industry, we discuss the economy a great deal, and we follow the statistics and economic measures: but what does it all mean and how do you use this information in your business? How does it help you make decisions, and how can you use it to answer your clients’ questions about the economy? In the news and industry articles there is a lot of noise: how do you know what matters, and what indicators will affect you and your clients, and the lenders you deal with.

In this article, we’ll explore what economic indicators matter most, and how to interpret them. We’ll cover how they affect the decisions lenders make that directly affect their offerings for your clients.

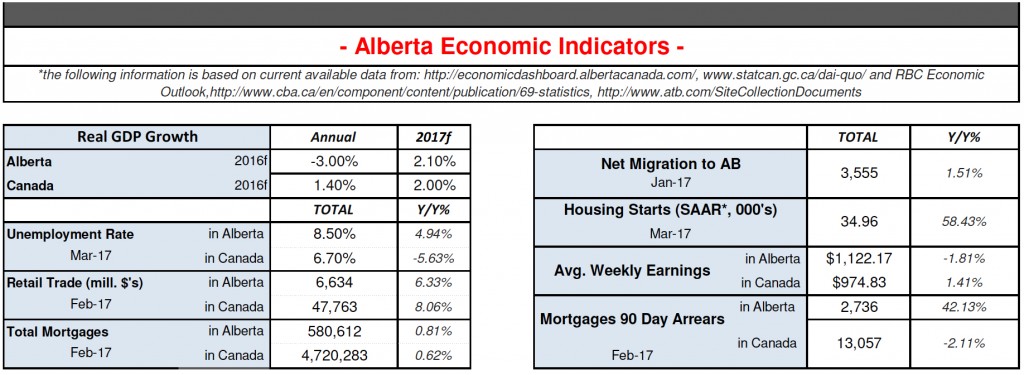

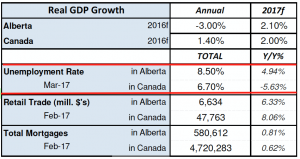

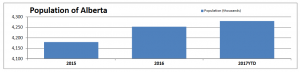

For the mortgage industry, the biggest and most important thing we follow is economic growth or contraction. Lots of things measure the growth of an economy, but the biggest indicator for a country or province is their GDP (Gross Domestic Product). This is basically a measure of how much the economy produces, either what we all spend as a group, or how much we all make, and whether it is growing or shrinking. I look at two major things here: what it has been, and what the professionals forecast it to be. I’m particularly interested in the local economy, such as the province, or major city. When an economy shrinks, we know that people are working less, making less, and spending less. In a growing economy, we are producing more, more of us are working, and we are generally spending or investing more.

The problem with GDP is that it takes a while to get it all calculated each quarter and year: so it is like looking back 2 or 3 months or even a year to see how our health is (WAS!) doing: it is not a great measure for today, which is why we also look for more current indicators of our economy’s health, such as our employment or unemployment to see how many are or are not working, or how much we are spending (retail trade, wholesale trade, and other indicators of spending). The difficulty of course with any one of these indicators is that they only tell part of the story, and we also have to remember that not all parts of the story will weigh equally in telling the conclusion of economic growth.

As a mortgage lender, the most important indicators for me, next to GDP, are employment and unemployment: if our borrowers are employed, they should not have difficulty making mortgage payments.

Within job growth, we look for stronger growth of full-time jobs compared to part-time jobs. Full-time work generally pays better and comes with a complete package of worker’s benefits. A higher proportion of full-time work better supports homebuyers entering the market, as well as current homeowners.

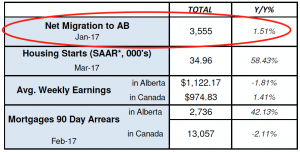

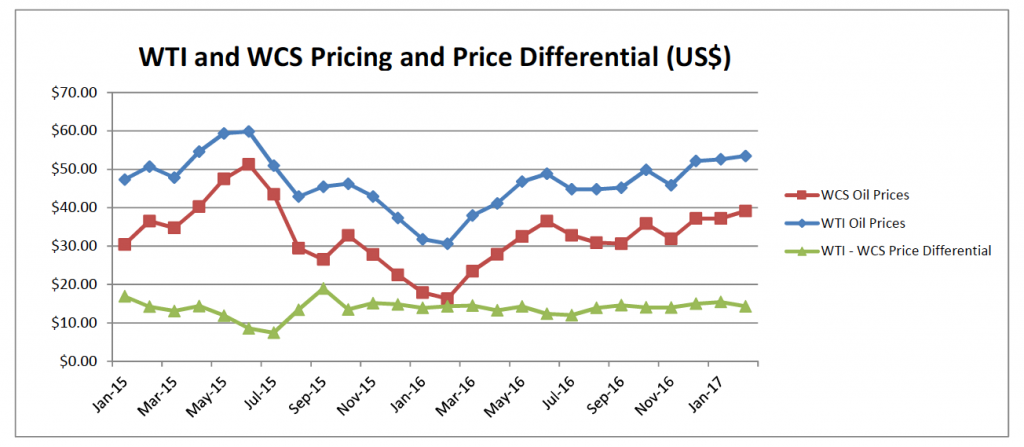

An important starting point in understanding the local economy is to understand what it is made up of. In other words, what are the main industries, local economic drivers, and commodities that a particular town, city or province are exposed to that affect local GDP, jobs, and local buying power. In Alberta, we spend a great deal of time talking about the oil and gas industry,

When the economy is doing well, lenders are better assured that risks are lowered. Borrowers are best positioned to make payments and less likely to run into financial difficulties. Should a borrower lose their ability to make timely payments, and mortgage arrears follow, the property may need to be sold. In a good economy, this sale is likely to happen relatively quickly, and for a strong price. A maxim that lenders know all too well is that lenders never participate in a borrower’s upside, only in their downside. A lender does not make more money because a borrower makes more money, or because their property is worth more; the lender can only make the money that the mortgage contract outlines. On the other side of the equation, if a borrower cannot make their payments, and the value of their property is not sufficient to cover their mortgage, the lender may lose. Managing that downside risk is always important for a lender.

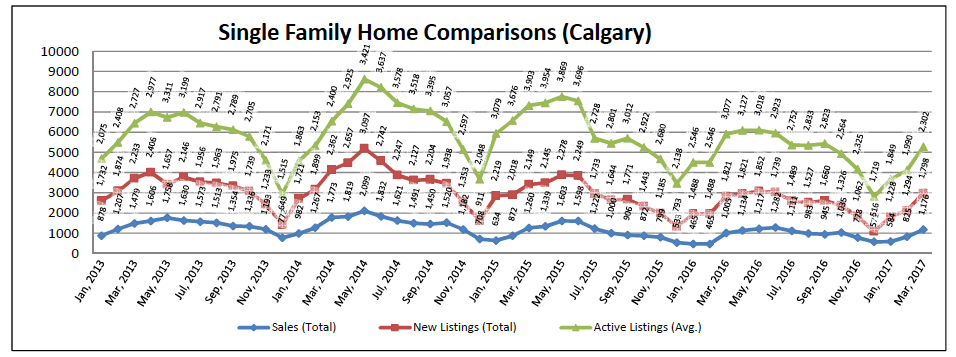

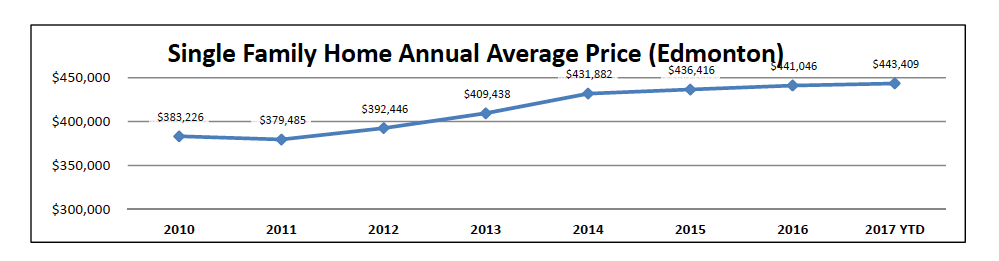

That brings us to what we watch in the real estate market to manage our mortgage business. Experts always say that all real estate is local, and so it is important for lenders to watch all the real estate markets that they are exposed to. That includes all those economic drivers we have already covered and extends to those variables on real estate supply, demand, and their resulting effect on prices. Real estate is no more complex than other commodities in terms of how supply and demand affect prices. How it is different is noteworthy though: no one property is identical to any other, even identical floor plan houses will have a location difference, and when it comes to the resale market, the differences between houses begin to be vast when variables such as maintenance, styles, streets and neighbourhoods change over time.

Every lender cares about the individual value of the property they are lending against, and once that decision is made and funds are lent, we watch the general market for both clues to see where the value of that asset is likely going, as well as helping us determine if the new loans we write are at the correct loan to value.

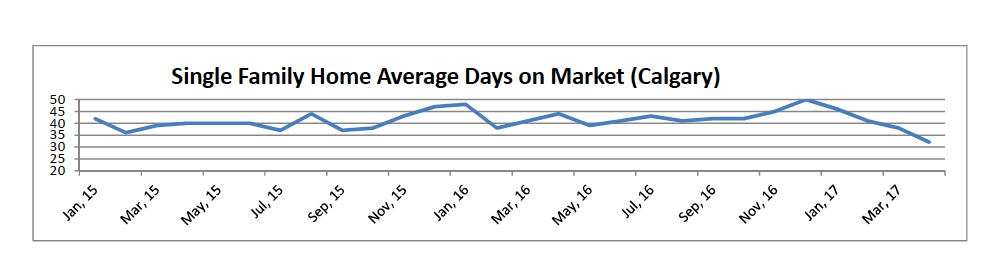

There is an annual cycle to the market in Alberta, as in most provinces, and supply as well as sales do tend to both increase in the spring market and trail off in the summer. So, it is important not simply to watch what supply is doing compared to the previous month, but compared to the previous year. We find it helpful to have this graphed to observe not just the trend compared to the previous year, but compared to several years past. Another clue to supply or demand trends is the average days on market listings experience.

Watching the market’s month to month trends are useful to see if it is following the trends we have experienced over the previous few months, and question whether you have a new change in trend. Some traders of certain commodities watch market trends on a minute by minute basis, but the real estate market is rarely able to be managed more frequently than a month by month basis. A relatively slow moving market for such an expensive commodity is reassuring to both buyers and sellers, as well as to lenders. To the extent that the housing market can have a level of volatility, it is important to point out that both communities and certain property price ranges can be more volatile than others. As a mortgage broker, you experience this when lenders cut back the loan to value offered in certain price ranges, or towns, outlying areas or acreages.

How can a lender manage their mortgages in the face of economic risk? A proactive way to manage risk is to react quickly by changing lending criteria as the economy shifts. The common levers we are all familiar with are credit scores, limiting mortgages for borrowers in specific industries, or job types, as well as limiting exposure to certain types of real estate. Favouring borrowers with stronger histories of income and job stability is another way to control go forward risks. Decreasing the total amount one borrower can borrow is another, such as limiting a real estate investor to only 5 doors. Some lenders will get even more specific in managing risks by removing entire product lines. Likely the single biggest factor to limit risk is by controlling the loan to value that money is lent at. The goal is to ensure that the real estate security will have sufficient value to more than cover the mortgage for no matter how long the mortgage stays on the books. The loan to value is controlled at the initial underwriting of the loan, and the only other time it can be controlled is at the maturity, where lenders can decide not to renew the loan.

A lender should watch the economic cycles it expects to see, and particularly watch for emerging trends that require more proactive risk management. Likewise, if a mortgage broker can do the same, they will not only appreciate why the lenders are making changes but also think ahead to the market segments they seek to market to and develop as clients.

If you’re interested in white-labeled version of our monthly Real Estate and Economic Report to send to your clients or have any thoughts or questions drop me a line at dale@chmic.ca